The long straddle is a non-directional option

strategy that can yield solid results with low

risk. It’s used when you expect a stock or

futures contract to make a big price move but

you don’t know whether it will be up or down.

Besides price, the other variables that affect the value of a

long straddle are volatility and time. A straddle’s value is

very sensitive to changes in implied volatility (IV). Also,

because a straddle consists of long options, its value erodes

a little bit each day (the process known as “time decay”).

After explaining how to construct a long straddle, we’ll

examine how to take into account the current volatility situation

and the effects of time decay when planning a trade.

Finally, we’ll compare two straddles that use options from

different expiration months to illustrate how buying more

time can create a trade with a higher probability of success.

Constructing a long straddle

A long straddle is created by purchasing equal numbers of

call and put options on the same underlying instrument

and with the same strike price and expiration month. It

makes sense to buy near-the-money options so a sharp

price move has a better chance of increasing the position’s

value. A large price move will make one of the legs deep in

the money, providing a gain by virtue of price movement

alone.

Also, an at-the-money straddle will be cheaper than a

straddle whose strike price is not equal to the stock price

because it consists of options whose values are composed

solely of time value (i.e., neither option has any intrinsic

value). Of course, you will not always find strike prices that

are identical to the current stock price, but you want

options that are as close as possible.

Buying undervalued options helps put the odds further in

your favor. The trick is to determine when options are

cheap. Options are undervalued when IV is low from a historical

perspective (that is, it is low compared to past IV

readings), as well as low relative to historical, or statistical

volatility (SV), which is the actual volatility of the stock.

Also, another reason to buy at-the-money options is changes

in IV will have a bigger impact on them with a few months

left to expiration.

Long straddles actually provide two ways to make money:

Either the underlying stock can make a big price move, or IV

can increase. Because volatility changes have such a big

impact on a straddle’s value, the next issue we will investigate

is how to find straddle candidates with historically low

IV levels, and how to measure the effect an IV increase has

on an option’s value.

Putting volatility in your corner

Placing a long straddle on a stock with historically low IV

can provide a considerable advantage. Every asset has quiet

periods when its options are cheap and volatile periods

when its options are expensive. You should also be aware

volatility has an important tendency called “reversion to

the mean.” After reaching extreme highs or lows, volatility

tends to return to a more “normal,” average level.

The first thing to look for when searching for likely straddle

candidates is the current IV compared to past IV. The

best candidates for long straddles are in the 10th percentile

of cheapness — that is, 90 percent of the time the IV has

been higher than it is currently. This increases the odds IV

will revert to a higher level, increasing the straddle’s value.

Different time periods can be used to calculate this percentile;

the past three years of volatility history is a good

place to start.

One way to measure IV in this way is to average the IV

levels of both calls and puts and then plot those averages on

a graph, with each data point representing a weekly average.

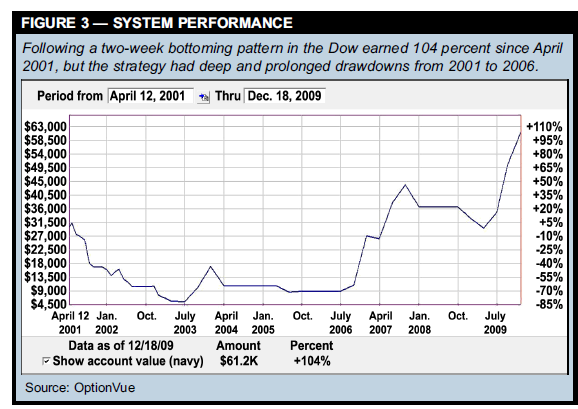

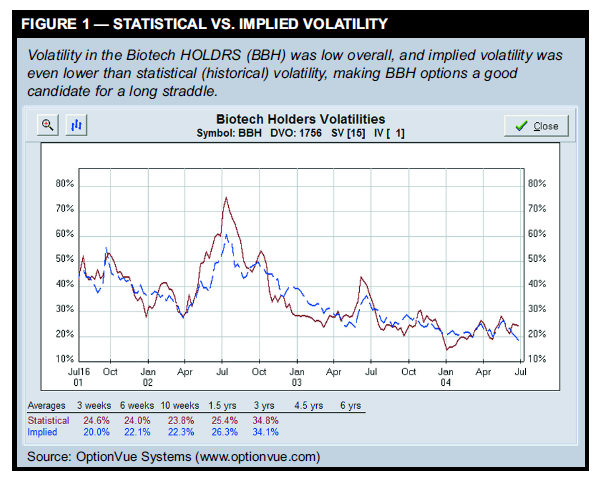

Figure 1 shows an example of a volatility chart for the

Biotech HOLDRS (BBH) that showed up as a likely straddle

candidate, which in early July had IV in the 1-percentile rank, meaning IV at this time was

lower than 99 percent of IV readings

over the past six years.

The volatility chart has two lines.

The solid line is statistical volatility

(SV), which shows the actual volatility

of the stock’s daily price changes. The

dashed line is the average IV, the

volatility implied by BBH option

prices. Not only was IV currently at its

lowest point since options began trading

on BBH, but it was also considerably

lower than SV (15 percentile

rank), indicating the option prices are

not even reflecting the actual volatility

of the stock.

Aposition’s sensitivity to changes in

IV is measured by vega, which is one of

the option “Greeks.” For ease of use,

vega is usually shown as the gain or loss a position would

experience because of a 1-percent IV increase. Long straddles

always have positive vega, which is why they are popular

for exploiting expected increases in IV. A long straddle’s

vega is highest when the stock price is identical to the options’ strike price.

The drawback of time

Options are a decaying asset, and as you get closer to expiration,

the rate of decay accelerates. The value of a straddle’s

long calls and puts constantly declines because of time

decay. As a result, to make a reasonable profit you need a

price move and/or an IV increase that can overcome the

time decay plus the initial purchase cost.

Theta is used to measure a position’s sensitivity to the

passing of time. It is usually expressed as the value a position

would lose in one day due to the effect of time alone.

Theta is always negative for a long straddle because the

options lose value as time passes.

Time decay doesn’t manifest itself immediately. A sixmonth

straddle does not decay much at first, and time

decay does not really begin to accelerate until the last

month or so before expiration.

Because volatility trades take time to develop, make sure

you give yourself enough time for IV to make the move you

expect. Look to use farther-out options, even LEAPS (Long-

Term Equity AnticiPation Securities, which are options that

can expire several years in the future), when buying straddles

to provide plenty of time for IV to revert to its average

level.

Choosing the best position

Many traders have difficulty understanding exactly how

option spreads become profitable. For a long straddle to be

profitable at expiration, the stock price must be sufficiently

higher or lower than the options’ strike price to give either

the call or put enough intrinsic value to offset the straddle’s

original cost. But before expiration, you must take into

account the simultaneous effect changes in the underlying

stock price, implied volatility, and time have on each leg of

the spread. For that reason, having access to a program that

allows you to analyze and graphically display the profit or

loss of a potential option trade is very important.

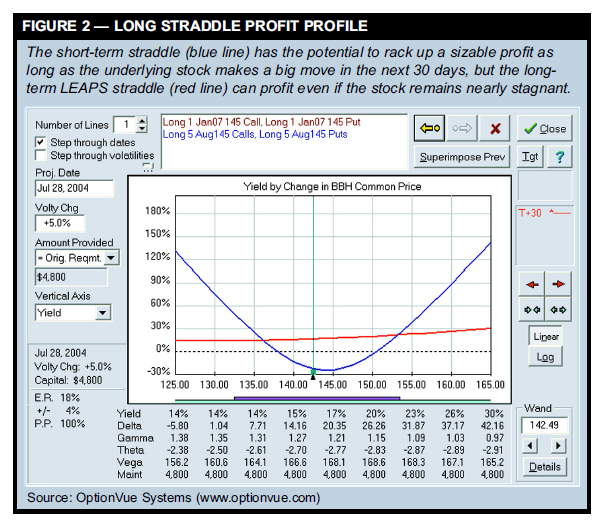

Let’s compare how profitable two long straddles in the

Biotech HOLDRS might be, one using the August 2004

options (with 54 days to expiration), and the other using the

January 2007 LEAPS (more than two years to expiration). In

early July, BBH was trading at 142.5, exactly halfway

between the available strike prices of 140 and 145.

Comparing the possible trades revealed using the 145 strike

price had a higher expected return.

The following trade examples used $5,000 as the maximum

amount of capital to invest, in each case buying as

many contracts as possible to keep the amount invested in

the trades as close as possible.

The shorter-term straddle position is:

Buy five August 145 calls (BBHHI) at $3.40 ($1,700)

Buy five August 145 puts (BBHTI) at $5.30 ($2,650)

Total cost: $4,350

The longest-term LEAPS straddle is:

Buy one January 2007 145 call (OEEAI) at $28.10 ($2,810)

Buy one January 2007 145 put (OEEMI) at $19.90 ($1,990)

Total cost: $4,800 The straddle using the August

options has a vega of 215.2 and a

theta of -37.5 when it is placed. The

vega/theta ratio is 5.7, which means

IV must rise 1 percent in only 5.7

days just for the position to remain

at breakeven. The straddle using the

January 2007 LEAPS has a 139.9

vega and a -2.92 theta, which translates

to a 47.9 vega/theta ratio,

which means IV only needs to

increase 1 percent every 47.9 days

for the position to stay even. Of

course, any price moves by the stock

would also affect the positions’ values.

Figure 2 shows what the two

trades would look like 30 days from

purchase with a projected IV

increase of 5 percent during this

time. It’s clear if you want to swing

for the fences and hope a large price

move occurs relatively quickly, you should use the shorterterm

options because you actually have the chance,

although small, of doubling your money in a short time

period. However, just to break even in 30 days — even with

a 5-percent IV increase helping out — the stock would have

to move down to $137.80 or up to $150.60. In other words,

to do better than the LEAPS straddle, BBH would have to

drop at least $6.19 or increase $10.51 in the next 30 days.

In contrast, notice the longer-term LEAPS straddle would

be profitable across the range of stock prices as long as IV

increased 5 percent. In fact, if the stock bounced around but

ended up right where it started at $142.50, you would still

make a 15-percent return (177 percent annualized), compared

to a 30-percent loss using the shorter-term options.

That shows just how important buying time can be in determining

your probability of placing a successful trade.

Deciding when to close a long straddle is subjective. If a

move in the underlying stock has created a gain, one leg

will now be worth much more than the other. The dominant

leg will then be much more sensitive to changes in the

underlying stock price. You should then determine if

volatility has returned to more normal levels, and consider

closing the position if it has.

Buying fairly valued options isn’t a bad thing

The argument many traders make against buying options is

time decay is against you, but there is nothing wrong with

buying an option that is fairly valued. Despite the drawback

of time decay, the underlying market is in constant motion.

In fact, time is precisely what gives the underlying stock or

future its freedom to move. You simply need to evaluate

whether the underlying instrument can move enough to

make a long straddle profitable.

Identifying stocks with inexpensive options puts the

odds further in your favor. Volatility traders often create

positions using short-term options, expecting volatility to

revert quickly to its mean. However, experience suggests

that’s a difficult expectation to meet. It can happen, but

cheap options often stay cheap for quite a while. When buying

long straddles, it’s a good idea to consider using the

longest-dated options available with decent liquidity.

Keep in mind the value of a straddle with more days until

expiration will not change as much as one with fewer days

left when the stock price moves up or down. The best straddle

for taking advantage of changes in IV is not going to be

the best one to capitalize on quick moves in the stock price.

Creating positions you’re comfortable with and understanding

how to balance likely price moves against theta

and vega are things you need to consider when trading

straddles. There are no sure things in option trading, but

understanding how a straddle works allows you to put the

odds in your favor when using this strategy

Call buying opportunities

Market: Options on the Dow Jones Industrial

Average (DJX).

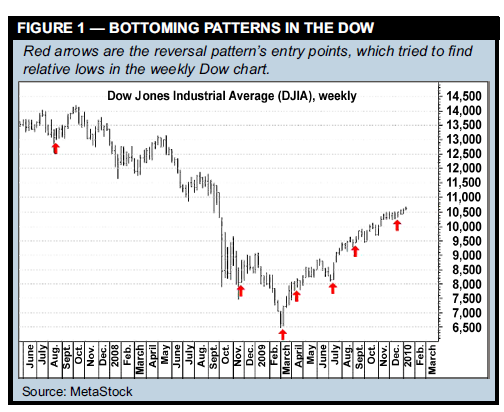

System concept: This options lab tests the

profitability of a technical pattern first identified

in the January issue of Active Trader

(“Hitting bottom,” p. 12). The pattern tries to

spot market bottoms in the Dow Jones

Industrial Average (DJIA), so the strategy

involves buying call options to take advantage

of an expected rebound.

The two-week pattern forms as the

Dow bottoms out. In the first week, the

market opens near the top of its range

before losing ground, and it reverses

direction in the second week.

Historical testing shows the Dow rose

sharply (and consistently) over the

next 12 weeks, suggesting it managed

to pinpoint some relative lows.

The formula for entry signals is:

1. (Open[2]-Low[2])/(High[2]-Low[2])

> .75

2. High[1]>High[2]

3. Low[1]>Low[2]

4. Close[1]>Close[2]

5. (Close[1]-Low[1])/(High[1]-Low[1])

> .75

Where: [0], [1], [2], refer to this week,

last week, and two weeks ago.

The pattern finds that weeks that

start strong and sometimes lose steam

are followed by weeks that bounce back and close even

stronger. Figure 1 shows this system’s bullish entry points

in the Dow since June 2007.

The trade rules simply buy 10 at-the-money (ATM) calls.

Because the pattern is based on a weekly chart and waits 12

weeks for the market to rebound, the strategy buys calls in

the first option expiration month with at least 90 days

remaining.

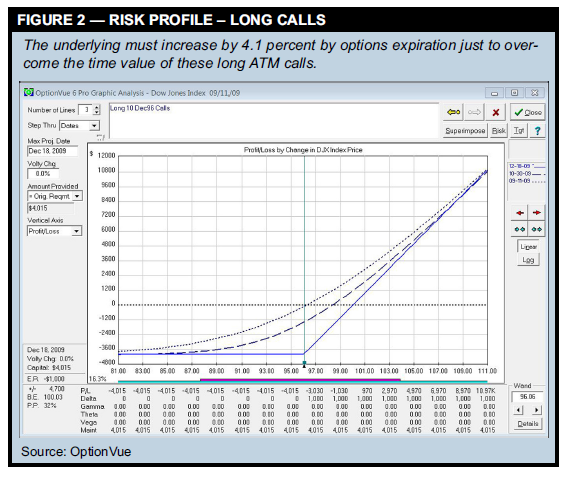

Figure 2 shows the potential gains and losses of a long

call entered on Sept. 11, 2009 when DJX was at 96.06 and

held through Dec. 18, 2009. The position of 10 long

December 96 calls cost $4,015 and would break even only if

the market climbed to 100.03 by expiration. If DJX finishes

below 96, the calls will expire worthless and lose their entire

cost ($4,015). Clearly, the underlying market needs gain

ground to overcome this time decay.

Trade rules:

1. When signal triggers on

Friday’s close:

2. Buy 10 ATM calls in first

month with at least 90 days

remaining before expiration.

Exit at expiration by letting the

calls expire worthless or

exercise into cash.

Starting capital: $30,000.

Execution: Option trades were

executed at the average of the bid

and ask prices at the daily close, if

available; otherwise, theoretical

prices were used. Commissions were $15 per trade.

Test data: The system was tested on cash-settled Dow

Jones index (DJX) options.

Test period: April 12, 2001 to Dec. 18, 2009.

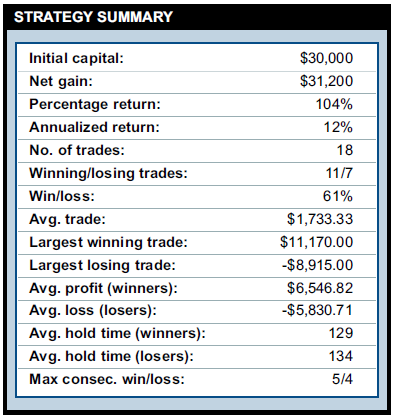

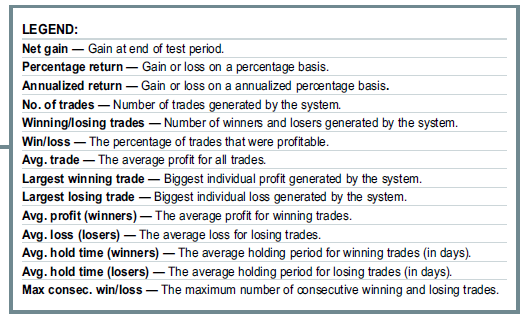

Test results: Figure 3 shows strategy gained $31,200 (104

percent) since April 2001, an annualized return of 12 percent.

The strategy’s average losing trade (-$5,830.71) was

less than its average winning trade ($6,546.82), but a losing

streak can quickly deplete your capital. The first four trades

in 2001 all lost money, and the drawdown grew to $24,510.

Overall, the system traded 18 times in eight and a half

years, 61 percent of which were profitable. Statistically,

ATM long calls have a probability of winning about 33 percent

of the time, so the system has a definite trading edge.

Note: The total number of trades (18) is a relatively small

number to base conclusions on. It would

require a great deal of courage to actually

trade such a volatile system.